All dictatorships like to proclaim patriotism but dictatorial patriotism is just an excuse to inflict disasters on the nation and calamities on its people.

— Liu Xiaobo, “The [Communist Party of China’s] Dictatorial Patriotism” (2005)

[China] provides large quantities of economic assistance to dictatorships such as North Korea, Cuba, and Myanmar, offsetting to some degree the impact of Western economic sanctions and enabling these remaining despotic regimes on their last legs to linger on.

— Liu Xiaobo, “The Negative Effects of the Rise of Dictatorship on World Democratization” (2006)

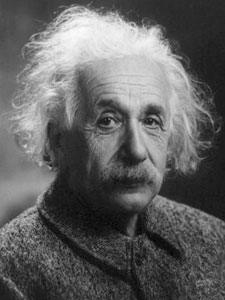

Liu Xiaobo (刘晓波), 54, the prominent independent intellectual and long-time democracy advocate, was awarded the Nobel peace prize on 8 October 2010, for his “long and non-violent struggle for fundamental human rights in China.” The first resident citizen of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) to win a Nobel prize, Liu becomes only the second person to win the peace prize while incarcerated, following German pacifist Carl von Ossietzky, who won it in 1935 while jailed by the Nazis. In its press release, the Norwegian Nobel Committee noted:

. . . [T]here is a close connection between human rights and peace. Such rights are a prerequisite for the “fraternity between nations” of which Alfred Nobel wrote in his will.

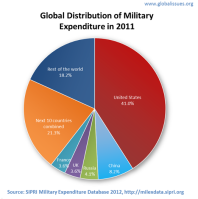

Over the past decades, China has achieved economic advances to which history can hardly show any equal. The country now has the world’s second largest economy; hundreds of millions of people have been lifted out of poverty. Scope for political participation has also broadened.

China’s new status must entail increased responsibility. China is in breach of several international agreements to which it is a signatory, as well as of its own provisions concerning political rights. Article 35 of China’s constitution lays down that “Citizens of the People’s Republic of China enjoy freedom of speech, of the press, of assembly, of association, of procession and of demonstration”. In practice, these freedoms have proved to be distinctly curtailed for China’s citizens.

For over two decades, Liu Xiaobo has been a strong spokesman for the application of fundamental human rights also in China. He took part in the Tiananmen protests in 1989; he was a leading author behind Charter 08, the manifesto of such rights in China which was published on the 60th anniversary of the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the 10th of December 2008. The following year, Liu was sentenced to eleven years in prison and two years’ deprivation of political rights for “inciting subversion of state power”. Liu has consistently maintained that the sentence violates both China’s own constitution and fundamental human rights.

The campaign to establish universal human rights also in China is being waged by many Chinese, both in China itself and abroad. Through the severe punishment meted out to him, Liu has become the foremost symbol of this wide-ranging struggle for human rights in China.

Liu is one of the leaders of the Independent Chinese PEN Centre (ICPC), a group of writers that promotes freedom of expression. The ICPC is among 145 member centers of the International PEN, a human rights organization and international literary organization founded in 1921. Liu’s writing is banned in China but his books are sold in Hong Kong. “Awarding Liu Xiaobo the Nobel Peace Prize is an affirmation of the central importance to everyone of freedom of expression, of which he is a courageous exponent,” states PEN International President, John Ralston Saul. “Charter 08 contains this phrase: We must stop the practice of viewing words as crimes,” says Marian Botsford Fraser, Chair of PEN International‘s Writers in Prison Committee. “Liu is serving 11 years for that simple credo, and his belief in democracy for the Chinese people. We fervently hope that Liu’s winning of the Nobel Prize furthers those causes.”

“Liu Xiaobo is a worthy winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, we hope it will keep the spotlight on the struggle for fundamental freedoms and concrete protection of human rights that Liu and many other activists in China are dedicated to,” said Catherine Baber, Amnesty International USA‘s Deputy Director for the Asia-Pacific region. “This award can only make a real difference if it prompts more international pressure on China to release Liu, along with the numerous other prisoners of conscience languishing in Chinese jails for exercising their right to freedom of expression”, said Baber.

Harry Wu, former Chinese political prisoner and founder of Laogai Research Foundation, said of the decision, “the Nobel Committee has sent a clear message to China that it will not be intimidated by its economic and political might.” He added, “for decades, Liu Xiaobo has advocated for freedom. It’s time that the Chinese government releases him from prison and listens to his suggestions.”

“This award comes at a critical historical crossroads in China and constitutes a powerful affirmation for the voices calling for change,” said Sharon Hom, Executive Director of Human Rights in China. “As Liu Xiaobo and other Chinese advocates for change have pointed out, the only sustainable road ahead for China is one towards greater openness and political reform. This has most recently even been publicly stated by senior Chinese officials [Ed.: See transcript of interview with Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao on 28 September 2010].”

I agree. Amnesty International has documented widespread human rights violations in China:

- An estimated 500,000 people are currently enduring punitive detention without charge or trial.

- Millions are unable to access the legal system to seek redress for their grievances.

- Harassment, surveillance, house arrest, and imprisonment of human rights defenders are on the rise.

- Censorship of the Internet and other media has grown.

- Repression of minority groups, including Tibetans, Uighurs and Mongolians, and of Falun Gong practitioners and Christians who practice their religion outside state-sanctioned churches continues.

- While the recent reinstatement of Supreme People’s Court review of death penalty cases may result in lower numbers of executions, China remains the leading executioner in the world.

Furthermore, the totalitarian nature of China’s government makes it nearly impossible to effect change in the notoriously oppressive government of North Korea (DPRK), essentially a puppet state of China. Human rights in China is a prerequisite to human rights in North Korea.

Not surprisingly, China’s foreign ministry last week warned that Liu was not suited for the Nobel Peace Prize as he was “sentenced to jail by Chinese judicial authorities for violating Chinese law.” The Chinese government told reporters the committee had violated its own principles by giving the award to a “criminal.” Of course, the Chinese don’t get it: Liu is a political prisoner, not a criminal. In the run-up to the decision, China warned Norway that selecting Liu would affect mutual ties and dispatched a Foreign Ministry official to Oslo to press its case. The two countries are in the process of negotiating a free-trade deal, and Norway’s oil industry — a crucial sector of its economy — wants to boost its business dealings in China. In a sign that it was unwilling to be cowed, however, Norway’s government chose to publicize the Beijing official’s ostensibly private visit.

____________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________

Liu was born on 28 December 1955 in Changchun, Jilin Province. He received a BA in literature from Jilin University, and an MA and PhD from Beijing Normal University, where he also taught.

In April 1989, he left his position as a visiting scholar at Columbia University to return to Beijing to participate in the 1989 Pro-Democracy Movement. On 2 June, Liu, along with Hou Dejian, Zhou Duo, and Gao Xin, went on a hunger strike in Tiananmen Square to protest martial law and appeal for peaceful negotiations between the students and the government. In the early morning of 4 June 1989, the four attempted to persuade the students to leave Tiananmen Square. After the crackdown, Liu was held in Beijing’s Qincheng Prison until January 1991, when he was found guilty of “counter-revolutionary propaganda and incitement” but exempted from punishment.

In 1996, he was sentenced to three years of Reeducation-Through-Labor on charges of “rumor-mongering and slander” and “disturbing social order” after drafting the “Anti-Corruption Proposals” and letters appealing for official reassessment of the June Fourth crackdown.

“There was never a question for him of abandoning the struggle, although he was very critical about the [1989 student] movement,” said Jean-Philippe Béja, of the Paris-based Centre for International Studies and Research, who first met Liu in the early 90s.

“He is a person who wants to live in truth.”

TAKE ACTION HERE: Demand that China release Nobel Peace Prize activist Liu Xiaobo!

AND HERE: Demand that China release Nobel Peace Prize activist Liu Xiaobo!

You must be logged in to post a comment.