The Price of Bananas:

On this date, the democratically-elected Guatemalan government of Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán was overthrown by CIA-paid and -trained mercenaries, making way for the United States to install a series of military dictatorships that waged a genocidal war against the indigenous Mayan Indians and against political opponents into the ‘90s. Human rights groups estimate that, between 1954 and 1990, the repressive operatives of successive military regimes murdered at least 100,000 and probably more than 200,000 civilians.

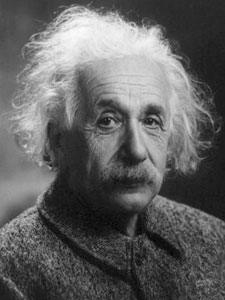

In a radio broadcast in July 1954, Arbenz said:

They have used the pretext of anti-communism. The truth is very different. The truth is to be found in the financial interests of the fruit company [United Fruit] and the other U.S. monopolies which have invested great amounts of money in Latin America and fear that the example of Guatemala would be followed by other Latin countries… I was elected by a majority of the people of Guatemala, but I have had to fight under difficult conditions. The truth is that the sovereignty of a people cannot be maintained without the material elements to defend it…. I took over the presidency with great faith in the democratic system, in liberty and the possibility of achieving economic independence for Guatemala. I continue to believe that this program is just. I have not violated my faith in democratic liberties, in the independence of Guatemala and in all the good which is the future of humanity.

United Fruit, one of America’s richest companies, functioned in Guatemala as a state within a state. It owned the country’s telephone and telegraph facilities, administered its only important Atlantic harbor and monopolized its banana exports. A subsidiary of the company owned nearly every mile of railroad track in the country.

The fruit company’s influence amongst Washington’s power elite was equally impressive. On a business and/or personal level, it had close ties to the Dulles brothers, various State Department officials and congressmen, the American Ambassador to the United Nations, and others. Anne Whitman, the wife of the company’s public relations director, was President Eisenhower’s personal secretary. Under-secretary of State (and formerly Director of the CIA) Walter Bedell Smith was seeking an executive position with United Fruit at the same time he was helping to plan the coup. He was later named to the company’s board of directors.

Furthermore, in the early 1940s, United Fruit had brought on as its public relations counsel Edward Bernays, a diminutive man who had proven his ability to act big by convincing a generation of American women to smoke the cigarettes made by his client American Tobacco Co., luring a generation of children into carving sculptures from Ivory Soap bars made by client Proctor and Gamble, and generally tapping the ideas of his uncle, Sigmund Freud, on why people behave the way they do, only to reshape those behaviors for the benefit of his paying customers.

Bernays helped mastermind the propaganda campaign for his fruit company client to convince Americans that Arbenz was a Communist threat to the U.S., drawing on every public relations tactic and strategy he had refined since helping to convince Americans that Germany was a threat to the U.S. during World War I.

_____________________________________________________

A singing, dancing Chiquita banana, modeled after Carmen Miranda, became the symbol for the United Fruit Company. Through this sexy banana symbol, Latin America was feminized, creating images in Americans’ minds of a colonial Latin America with an indigenous population of topless women, which was of course not the case.

_____________________________________________________

The Eisenhower Administration painted the coup as an uprising that rid the hemisphere of a Communist government backed by Moscow. But Arbenz’s real offense was to confiscate unused land owned by the United Fruit Company to redistribute under a land reform plan and to pay compensation based on the vastly understated valuation the company had claimed for its tax payments. Arbenz “was not a dictator, he was not a crypto-communist,” said Stephen Schlesinger, an adjunct fellow at the Century Foundation and co-author of Bitter Fruit: The Story of the American Coup in Guatemala (1999). “He was simply trying to create a middle class in a country riven by extremes of wealth and poverty and racism,” Schlesinger said. Both Arbenz and his immediate predecessor, Juan Jose Arevalo, who was the first democratically-elected Guatemalan president, were motivated by the policies and practices of the New Deal; their support for labor and their actions towards American businesses must be viewed in this light and were never any worse than those of the Roosevelt Administration during the Depression in the United States.

In 1970, the United Fruit Company merged with AMK Corporation; the new corporation was called the United Brands Company. This company became Chiquita Brands International in 1990.

On 10 March 1999 during remarks made in the Reception Hall in the National Palace of Culture in Guatemala City, President Bill Clinton apologized for U.S. support of the Guatemalan military (but not for the 1954 coup), saying U.S. “support for military forces or intelligence units which engage in violent and widespread repression of the kind described in the report was wrong”. He was forced into this “damn-near” apology after the U.N.’s independent Historical Clarification Commission (Spanish: Comisión para el Esclarecimiento Histórico, or CEH) issued a nine-volume report called Guatemala: Memory of Silence [Conclusions and Recommendations archived here] on 25 February 1999.

Created as part of the 1996 peace accord that ended Guatemala’s civil war, the CEH and its 272 staff members interviewed combatants on both sides of the conflict, gathered news reports and eyewitness accounts from across the country, and extensively examined declassified U.S. government documents. The CEH concluded that for decades, the U.S. knowingly gave money, training, and other vital support to Guatemalan military regimes that committed atrocities as a matter of policy, and even “acts of genocide” against the Mayan people.

However, the Commission’s findings weren’t really news at all. That the Guatemalan military committed genocide and widespread atrocities had been widely known for many years. That the U.S. supported and trained the Guatemalan military had been a matter of public record. What was new here was the depth of documentation, and that the information was coming from an official source.

The CEH attributed 93% of the atrocities and 626 massacres to government forces, while only 3% of the atrocities were attributable to the guerrillas. (Responsibility for the remaining 4% could not be assigned with certainty.) Out of 200,000 documented victims, the CEH report found that 83% were indigenous. And worse, the vast majority of victims were non-combatant civilians. Merely trying to form an opposition political party was reason enough to be killed. So was being a trade unionist, a student or professor, a journalist, a church official, a child or elderly person from the same village as a suspected rebel, a doctor who merely treated another victim, or even a widow of one of the disappeared simply asking for the body.

Civil patrol members in northern Guatemala in March 1982. Civil patrols were established using local men forcibly conscripted by the government. This patrol had recently been supplied with U.S.-made M-1 rifles, replacing their former shotguns and machetes.

In fact, the same day that Clinton issued his damn-near apology, new documents obtained by the National Security Archive — a non-profit group of truth-seekers who do tremendous work obtaining and analyzing the internal records of things we aren’t supposed to know — were released that indicate that the U.S. was more intimately involved with the Guatemalan paramilitary than even the CEH report indicated.

These new documents proved irrefutably that as early as 1966, officials from the U.S. State Department, far from opposing the torturers, set up a “safe house” for security forces in Guatemala’s presidential palace, which eventually became the headquarters for “kidnapping, torture… bombings, street assassinations, and executions of real or alleged communists.” CIA documents also proved that from the very beginning, U.S. intelligence was fully aware that “disappearances” were actually kidnappings followed by summary executions. Rather than act to stop the slaughter, however, the U.S. State Department continued to provide tens of millions of dollars in aid. Once Ronald Reagan was elected president, covert money and support for the Guatemalan dictatorship soared, as did the atrocities. In fact, Reagan was the U.S. official most culpable for aiding and abetting the Guatemalan genocide.

In a muted ceremony at the National Palace in Guatemala City on 20 October 2011, Guatemalan President Alvaro Colom turned to Arbenz’s son Juan Jacobo and asked for forgiveness on behalf of the state for the overthrow of his father in 1954. “That day changed Guatemala and we have not recuperated from it yet,” he said. “It was a crime to Guatemalan society and it was an act of aggression to a government starting its democratic spring.”

On 21 October 2011, the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR) and the organization Rights Action issued an open letter to President Obama [archived here] asking the administration to follow the example of the Guatemalan government and issue an apology on behalf of the U.S. government for its role in the coup d’état and subsequent human rights violations perpetrated by the Guatemalan state. It stated:

The willingness of the United States to support illegitimate governments in Latin America did not begin and unfortunately did not end with Guatemala. In fact, Guatemala was one of the most atrocious but still just one of the bloody, repressive and destabilizing interventions in Latin America and the Caribbean that the U.S. government supported over the last century. Unfortunately, this interventionism continues today. Your October 5, 2011 White House meeting with and pledged support for President Porfirio Lobo of Honduras in the aftermath of the June 2009 coup d’état and the subsequent illegitimate elections there is a cogent example of the United States’ continued wrongheaded policy approach to Latin America. Honduras is engulfed in a wave of politically motivated violence where scores of opposition activists and journalists have been murdered since the coup. Support for the repressive Lobo government is in direct contradiction to the nationwide peoples’ movement of Honduras which is demanding an end to impunity for the repression against their movement and accountability for the 2009 coup d’etat.

CCR and Rights Action concluded the letter by urging President Obama to change the course of his administration’s foreign policy in Latin America and to put his words into action by ceasing to actively undermine Latin American peoples’ right to peacefully choose their leaders democratically and have these decisions be respected by the United States.

Bodies of some of the 20 villagers killed near Salacuin, in northern Guatemala, in May 1982. The Guatemalan army blamed leftist guerrillas for this massacre; survivors of other attacks carried out in the same region during this period blamed the army.

On 12 January 2012, Efrain Rios Montt, former head of state of Guatemala from March 1982 to August 1983, the bloodiest period in its history, appeared in a Guatemalan court on charges of genocide. During the trial, the government presented evidence of over 100 incidents involving at least 1,771 deaths, 1,445 rapes, and the displacement of nearly 30,000 Guatemalans during his 17-month rule. The evidence clearly showed that Ríos Montt had ordered soldiers to burn indigenous villages and kill Mayans.

On 10 May 2013, Rios Montt was found guilty and sentenced to 80 years in prison. The verdict was the first time in history in which a former head of state had been found guilty of genocide by a national tribunal in his or her own country. However, the victory was short-lived. On May 20, Guatemala’s highest court, the Constitutional Court, vacated the verdict against Ríos Montt and annulled all the legal proceedings that had taken place after April 19; a retrial may possibly occur in January 2015. During the week following Montt’s conviction, there had been forceful and repeated calls from CACIF, Guatemala’s powerful business association, for the verdict to be overturned, explicit threats made by Rios Montt’s lawyer of national paralysis if the Constitutional Court did not rule in Rios Montt’s favor, and bomb threats at the Constitutional Court and other government offices. Guatemala has to now decide if it wants to be known throughout the world as “The Land of Eternal Spring” or as “The Land of Eternal Impunity.”

As for Chiquita Brands International, it is just as corrupt as its predecessor.

In the late 1990s, in one of many chapters in the Colombian government’s decades-old dirty war with leftist guerrillas, more than 15,000 people in the northern region of Curvaradó were forced from their land. Those that followed were las mocha cabezas, meaning “the beheaders” — paramilitary death squads fighting as the military’s proxies. Thousands fled their massacres, bombardments, and executions. Behind the beheaders came the agribusinesses, which converted the territory into African palm plantations and cattle ranches under paramilitary protection. Thus began the cozy relationship between the corporations and the paramilitaries.

Chiquita had been operating in Colombia since the early 1960s through a wholly-owned subsidiary called “Banadex”. Between 1997 and 2004, officers of Banadex paid approximately $1.7 million to the right-wing United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (Spanish: Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia, or AUC) in exchange for local employee protection in Urabá, a region north of Curvaradó. The AUC has been responsible for some of the worst massacres in Colombia’s civil conflict and for a sizable percentage of the country’s cocaine exports, although they are fighting the guerrilla insurgency in order to preserve the political and economic status quo in Colombia. No later than September 2000, Chiquita’s senior executives knew that the corporation was paying the AUC and that the AUC was a violent, paramilitary organization. Similar payments were also made to the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) as well as the National Liberation Army (ELN) from 1989 to 1997, both leftist guerrilla organizations, as control of the company’s banana-growing area shifted. Not only were the FARC and ELN targeting U.S. personnel, they were also fighting against U.S. political and economic interests in Colombia.

The FARC and the ELN were placed on the U.S. State Department’s list of Foreign Terrorist Organizations in 1997, while the AUC was added in 2001; on 14 March 2007, Chiquita Brands said it had agreed to a $25 million fine as part of a settlement with the U.S. Justice Department for having ties to them. The plea agreement [archived here] claimed that the company had never received “any actual security services or actual security equipment in exchange for the payments” (see paragraph 23). Chiquita instead characterized itself as a victim of “extortion”.

But court documents subsequently obtained by the National Security Archive from the Justice Department and released as “The Chiquita Papers” in April 2011 show conclusively that Chiquita Brands International had, in fact, benefited from its payments — extorted or otherwise — to Colombian paramilitary and guerrilla groups. According to a 1994 legal memo, the general manager of Chiquita operations in Turbó admits that guerrillas were “used to supply security personnel at the various farms.” In a March 2000 memo, Chiquita lawyers describe a conversation with a company manager who said that it was absolutely necessary to make payments to right-wing paramilitary groups, not because of intimidation, but rather because they “can’t get the same level of support from the military.” It is still not known why U.S. prosecutors overlooked this clear evidence of culpability that they had in their possession while they were pursuing the case against Chiquita.

Even before “The Chiquita Papers”, there were other indications that the 2007 plea agreement was dishonest. On a broadcast of the U.S. news program 60 Minutes of 11 May 2008 [transcript archived here], correspondent Steve Kroft interviewed Salvatore Mancuso, former supreme leader of the AUC, in a Colombian maximum-security prison. Mancuso said the multinational Chiquita Brands agreed to pay the paramilitaries for their safety without threats:

Kroft: Chiquita says the reason they paid the money was because your people would kill them if they didn’t. Is that true?

Mancuso: No it is not true. They paid taxes because we were like a state in the area, and because we were providing them with protection which enabled them to continue making investments and a financial profit.

Kroft: What would have happened to Chiquita and its employees if they had not paid you?

Mancuso: The truth is, we never thought about what would happen because they did so willingly.

Kroft: Did [the company] have a choice?

Mancuso: Yes, they had a choice. They could go to the local police or army for protection from the guerrillas, but the army and police at that time were barely able to protect themselves.

Kroft: Was Chiquita the only American company that paid you?

Mancuso: All companies in the banana region paid. For instance, there was Dole and Del Monte, which I believe are U.S. companies.

Kroft: Dole and Del Monte say they never paid you any money.

Mancuso: Chiquita has been honest by acknowledging the reality of the conflict and the payments that it made; the others also made payments, not only international companies, but also the national companies in the region.

Kroft: So you’re saying Dole and Del Monte are lying?

Mancuso: I’m saying they all paid.

Kroft: Has anyone come down here from the United States, from the U.S. Justice Department, to talk to you about Dole, or to talk to you about Del Monte or any other companies?

Mancuso: No one has come from the Department of Justice of the United States to talk to us. I am taking the opportunity to invite the Department of State and the Department of Justice, so that they can come and so I can tell them all that they want to know from us.

Kroft: And you would name names?

Mancuso: Certainly, I would do so.

Mancuso had helped negotiate a deal with the Colombian government in 2003 that allowed more than 30,000 paramilitaries to give up their arms and demobilize in return for reduced prison sentences. As part of the deal, the paramilitaries must truthfully confess to all crimes, or face much harsher penalties. Since the interview aired, other jailed paramilitary leaders have corroborated Mancuso’s claims that they received protection money from Chiquita. At the time of the interview, Mancuso had been indicted in the U.S. for smuggling 17 tons of cocaine into the country. On 13 May 2008, Mancuso, along with 13 other paramilitary warlords, was unexpectedly extradited to the United States allegedly for failing to comply with the peace pact.

To distance itself from the scandal, Chiquita in June 2004 sold off its Colombian subsidiary, Banadex, which had provided the company with approximately 11 million crates of bananas every year. The company also partnered with Rainforest Alliance, which certified that all of Chiquita’s farms had fair health, labor, and environmental practices. However, Banadex was bought by Invesmar, the British Virgin Islands-registered conglomerate that is the holding company of a Colombian banana producer and exporter called “Banacol”. The $51.5 million deal included an agreement that Banacol would supply Chiquita with 11 million crates of bananas every year through 2012. And low and behold, Banacol in 2011 was Chiquita’s largest global supplier, accounting for 10 percent of Chiquita’s banana purchases, according to Chiquita’s annual statement to shareholders.

When the displaced communities first began to return to Curvaradó in 2002, they found a desert of African-palm plantations and cattle ranches in place of the small farms that once dotted their land. Most of the palm crops are now dead — killed by a mysterious fungal plague — and a number of the businessmen involved in colluding with the paramilitaries are in prison, under investigation, or on the run. However, as the palm trees have withered, the banana companies have advanced. In 2009, Banacol announced plans for a government-backed $6.4 million project planting 2,470 acres of plantain in Curvaradó for sale on international markets.

A legal complaint [archived here] against Chiquita filed before a U.S. federal court in Washington on 22 March 2011 on behalf of victims of the AUC claims that the former Banadex management now runs Banacol, that workers continued under Banadex contracts as late as 2009, and that the farms sold to Banacol — which make up over 70 percent of Banacol’s Colombian land — continue to supply Chiquita. “Banacol has acted as [Chiquita’s] alter ego since 2004,” the complaint concludes (see paragraph 870). The new accusations have arisen in the Curvaradó region of Colombia, where the Rainforest Alliance says it does not certify Banacol farms as environmentally and socially responsible.

While Chiquita’s payments to the AUC ended by 2004, Banacol continued paying security companies that were used to launder payments to the paramilitaries until at least 2007, according to details from a Colombia Prosecutors Office investigation of Chiquita, Banadex, and Banacol, which was leaked to the press in 2009.

In Colombia, it is apparently business as usual for Chiquita Brands International.

References:

- James Bargent, “Chiquita Republic: United Fruit’s heir has again been linked to paramilitary abuses in Colombia,” In These Times, 7 January 2013. Accessed on 5 July 2013 at http://inthesetimes.com/article/14294/chiquita_republic/.

- William J. Clinton: “Remarks in a Roundtable Discussion on Peace Efforts in Guatemala City,” 10 March 1999. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=57227.

- Nick Cullather. Secret History: The CIA’s Classified Account of its Operations in Guatemala, 1952-1954 (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 1999).

- Piero Gleijeses. Shattered Hope: The Guatemalan Revolution and the United States, 1944-1954 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992).

- Kevin Gray, “The Banana War,” Upstart Business Journal, 17 September 2007. Accessed on 5 July 2013 at http://upstart.bizjournals.com/news-markets/international-news/portfolio/2007/09/17/Chiquita-Death-Squads.html?page=all.

- Bob Harris, “Guatemala: Bill Clinton’s Latest Damn-Near Apology” The Humanist, May/June 1999. Accessed on 2 July 2013 at http://www.motherjones.com/politics/1999/03/guatemala-bill-clintons-latest-damn-near-apology.

- Interchurch Justice and Peace Commission. Columbia: Banacol (Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Transnational Institute, 18 September 2012). Accessed on 5 July 2013 at http://www.tni.org/report/colombia-banacol. Archived here.

- Elisabeth Malkin, “Former Leader of Guatemala Is Guilty of Genocide Against Mayan Group” New York Times, 10 May 2013. Accessed on 4 July 2013 at http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/11/world/americas/gen-efrain-rios-montt-of-guatemala-guilty-of-genocide.html?_r=0.

- National Archives – “U.S. Warns Russia to Keep Hands off in Guatemala Crisis” – National Security Council. Central Intelligence Agency. (09/18/1947 – 12/04/1981). – This film contains footage of Henry Cabot Lodge’s warning to the Soviet Union to not interfere in the political unrest in Guatemala. [Lodge was a major stockholder in United Fruit and had been a strong defender of the company while a U.S. senator.]

- John Prados. Safe for Democracy: The Secret Wars of the CIA (Ivan R. Dee, Publisher, 2006).

- Stephen Schlesinger and Stephen Kinzer. Bitter Fruit: The Story of an American Coup in Guatemala (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1999) [originally published in 1982 as Bitter Fruit: The Untold Story of the American Coup in Guatemala].

- Staff, “Chiquita Continues in Columbia,” El Espectador, 5 September 2009. Accessed on 5 July 2013 at http://www.elespectador.com/impreso/judicial/articuloimpreso159808-chiquita-sigue-colombia.

- U.N. Commission for Historical Clarification. Guatemala: Memory of Silence – Report of the Commission for Historical Clarification: Conclusions and Recommendations (25 February 1999).

You must be logged in to post a comment.